China's Gaza Moment

Rose blooms without flowers 《无花的蔷薇之二》: Lies written in ink can never conceal the facts written in blood. 墨写的谎说,决掩不住血写的事实。

*

By the time of Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth (1931), and 30 years after the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901), Chinese sentiments against western colonial presence in China had spread far and wide. So, it was strange that it should escape Buck’s attention an event that came to be known in Chinese as 三·一八惨案 The March 18 Massacre.

That day 5,000, most of whom were from 80 high schools and universities, had gathered at Beijing’s present day Tiananmen Square to demand that the post-Qing government:

(a) repudiate the 1901 Treaty of Xinchou 辛丑条约, commonly referred in English as the Boxer Protocol,

(b) annulled all special and extra-territorial legal treatment granted to foreigners under the dynasty-era government, and

(c) withdrawal of foreign troops camped throughout and besieging many of the coastal port cities.

Deployed under the Xinchou terms, those armies were drawn from, other than Japan, at least seven western nations: Britain, US, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Russia.

More traumatic and longer-term in effects were the treaty’s financial demands. Of these, the most damaging was the extraction from Qing China 450 million taels of silver payable in 39 yearly installments to 1940. Also payable, but half yearly, were interests fixed at 4 percent a year. By 1926, China had paid 980 million taels (present prices US$18.6 billion). Because China had run out of silver by then, the Allied Powers demanded for gold in lieu, counted on the same silver weight!

War-time records were sketchy but when China completed payment in 1940 it had enriched the West, in present-day exchange rates, US$2.1 trillion in gold and silver equivalent. And this sum was from a destitute population which, another 40 years later in 1980, was among the world’s ten poorest.

At the Tiananmen gate where hangs today the portrait of Mao Zedong, local troops under orders of the Japanese legation in 1926 were lined up several rows deep facing the demonstrators. Then they opened fire into the crowd, after which one poem lamented (see Note 2):

地流赤血成血洼 / 死者血中躺 / 伤者血中爬! The ground bleeds in puddles / In blood the dead lay / In puddles of blood the injured crawls!

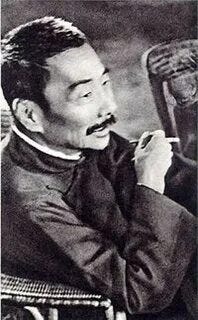

When word of the massacre — 47 dead, over 200 injured — reached the writer Lu Xun 魯迅, he was some way through an essay he was writing. He subsequently titled it: 无花的蔷薇之二〔1〕Rose Blooms Without Flowers:

这不是一件事的结束,是一件事的开头。

墨写的谎说,决掩不住血写的事实。

血债必须用同物偿还。拖欠得愈久,就要付更大的利息!

A century later, the same essay would gained notoriety online in Chinese websites where it was resurrected and redistributed following the massacres in Gaza. More important, though, is that it was directly relevant to Palestine: the foreign presence of Israel on their land, the subjugation of the natives, multiplied a hundred times over 1926. Applied to Gaza, Oct 7, 2023 the essay translates as:

This is not the end but the beginning of … something. Lies written in ink can never conceal the facts written in blood. Blood debts must be paid in kind. The longer one is in arrears, the greater is the interest accrued on day of repayment!

Notes:

For an example of a Chinese online comment, see: https://weibo.com/1157864602/Nnv11nnyt?type=repost

See: http://book.sina.com.cn/today/2010-10-21/162825978.shtml

For an online reading of Lu Xun’s 1926 essay (in Chinese only): 无花的蔷薇之二 https://www.marxists.org/chinese/reference-books/luxun/09/012.htm

Below: Tiananmen scenes before troops opened first; some the university students who died in the 1926 massacre — 魏士毅, 刘和珍, 杨德群; memorial stone; and Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881-1936, birth name 周樹人 Zhou Shuren)