The Death of the Rich: China's Lesson Consorting with the World's First Private Financier

China's reforms from 1980 focused solely on poverty. Now, some 40 years later, the same reforms must deal with its opposite: Wealth. Therein is the problem: What the fuck do you do with the Rich?

*

TO RESTORE CHINA, FIRST DESTROY AMERICA

This is Part 2, probably final part, in the continuation of the Series, Decision from the Third Plenum. First part is here. The title above corrects a deficiency of the Decision’s agenda logic. The correction is this: to restore China completely requires, as corollary, the destruction of the thing that torpedoes its effort at every turn and undermining it, namely America, the barbarian riding in from the West and the world’s most evil nation. The US is the Xiongnu-Hun of today, whose total destruction by the Han government left China safe and intact to develop for 2,000 years. This essay is about destroying America, centered on its domestic agents, their Anglophile underlings and the Rich.

*

*

Introduction: Lu Buwei and the Problem of the Rich.

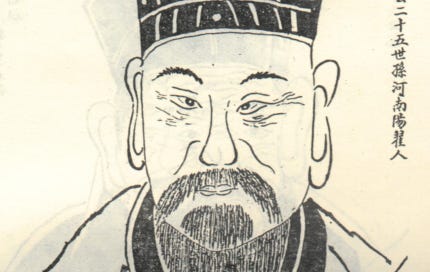

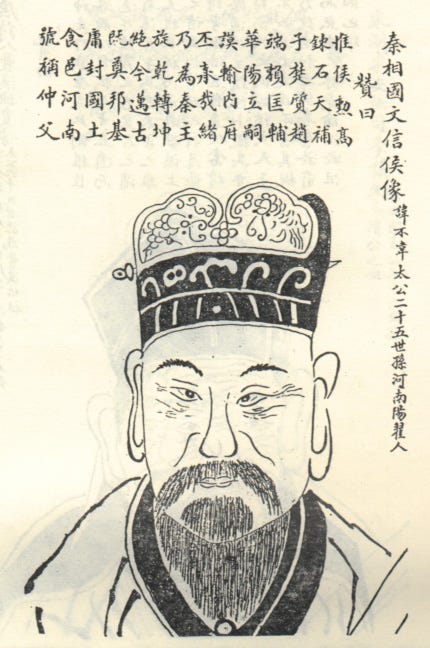

Much of what we know about Lu Buwei (above and below) comes from two primary sources: Sima Qian’s shiji 史記, commonly called in English, the Records of the Grand Historian, and Pan Gu’s hanshu 漢書 or Book of Han, both written 2,000 years ago. Unlike many senior public officials who usually get a footnote or little mention, Lu was written about extensively because he simultaneously wielded wealth and power. That is, he became a problem in politics and in governance instead being of a solution thereof, which was the initial thought.

The above image is a portrait print of a woodblock carving of Lu Buwei. Because of its script style, it is likely to have come from the Han era, 202 BCE to 220 CE. Lu’s role is still being debated today, appearing in the TV 78-part series (images below): Did he do more harm than good? How had he contributed to China’s unification, and so on. You can watch the series here 大秦帝国之裂变, titled in the English as The Qin Empire. (The film was intended solely for a Chinese audience, so you need some elementary, historical knowledge of Chinese civilizational culture, language, social relations, etiquette, dynastic government and politics to even make sense of anything because the sub-titles will only confuse you more.)

*

*

*

*

*

THE ONE COUNTRY, TWO EMPERORS PROBLEM

Were Lu Buwei 呂不韋, 291–235 BCE, to be alive today, his wealth would be comparable to Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager reputedly handling some USD9 trillion of assets dispersed over land, grain, equity stocks, transport and so on. The equal of the combined GDP of Germany, Japan and Saudi Arabia, USD9 tn is bigger than all individual economies, except the US (USD27 tn) and China (USD18 tn).

But, money aside, Lu (291-235 BCE), was better off than Fink in one respect though the former didn’t buy and sell equities or traded government bonds. He oversaw an entire government, its bureaucracy and ran a whole State — almost single-handedly.

For 14 years to 235 BCE, Lu was prime minister (also translated as chancellor) of the Chinese state of Qin (760 BCE-206 BCE), the most formidable State to emerge in the final decades of the Zhou government, 1046 BCE-256 BCE. It was essentially a Zhou offshoot. Before that he was personal instructor to Ying Zheng 嬴政, subsequently the Qin emperor commonly known in English as Qin Shihuang. He continued to be premier (or chancellor) when Ying Zheng took over the State and government from his father in 247 BCE.

Therein was the trouble, which in China since the Qin became known as One Country, Two Emperors problem: Who is ultimately in charge? How much in taxes to collect? Set policies? Determine war and peace?

The term One Country, Two Emperors appeared during the Spring and Autumn period, 770–476 BCE, when in the periphery of China’s main Zhou dynasty, 1046 BCE-256 BCE, a half a dozen relatively minor states such as Qin competed with Zhou for power over all China.

From the neighboring State of Qi (not to be confused with Qin), Lu Buwei’s contemporary and peer, its prime minister Guan Zhong 管仲 was observing events next door. Even long after Qin had vanquished the State of Qi, Lu Buwei’s reputation remained intact, a quite revolutionary political figure and official given his low social status background as merchant, financier and capitalist. Guan Zhong’s record of observations finally appeared in book form titled Guanzi 《管子》.

This, below, is what Guan Zhong had to say, in obvious reference to the world’s first capitalist financier Lu Buwei, 2000 years before Karl Marx talked about the petty bourgeoisie, social relations of production and surplus value (skip if you don’t read Chinese):

“ 译文:管仲说:“万乘之国如有万金的大商人,千乘之国如有千金的大商人,百乘之国如有百金的大商人,他们都不是君主所依靠的,而是君主所应剥夺的对象。所以,为人君而不严格注意号令的运用,那就等于一个国家存在两个君主或两个国王了。”桓公说:“何谓一国而存在两个君主或两个国王呢?”管仲回答说:“现在国君收税采用直接征收正税的形式,老百姓的产品为交税而急于抛售,往往降价一半,落入商人手中。这就相当于一国而二君二王了。所以,商人乘民之危来控制百姓销售产品的时机,使贫者丧失财物,等于双重的贫困;使农夫失掉粮食,等于加倍的枯竭。故为人君主而不能严格控制其山林、沼泽和草地,也是不能成就天下王业的。” — 《管子·轻重甲篇》,黎翔凤:《管子校注》(下),中华书局2004年版,第1425~1426页。参见《史记》卷6《秦始皇本纪》,许嘉璐主编:《二十四史全译·史记》(第一册),汉语大词典出版社2004年版,第77页。

The above passage split down the middle, I have inverted their logical order which in translation (mine) read as follows:

Guan Zhong speaks: “Now, the emperor [ruler] directly collects taxes [from the population], and this is positive. To pay the taxes, ordinary people have to sell their goods which they eagerly do so but to the merchants, if the latter can cut their prices by half. … So, in a bountiful nation is a certain merchant of plenty, with a thousand pieces of gold. [Ed: Lu Buwei had that reputation, as told by Sima Qian and Pan Gu.] Neither people nor merchant are now dependent on the emperor who is further deprived of taxes [by the merchant]. In the circumstances, people don’t strictly care for your orders even if you are emperor. Doesn’t this amount to the presence of two emperors in one nation.” [Guanzi Annotations. Brief synopsis. Common in Chinese publishing, Annotations serve as a compendium to the original work written decades, sometimes centuries earlier, in this case, Guanzi. Though the original observes and follow events, c. 770 BCE to 476 BCE but, at its republishing centuries later, usually copying still in long hand ink brush on cut bamboo strips, the original required elucidations and explanations (at it is being done here in italics) using scattered and unpublished notes of the author Guan Zhong. That republished original, along with the Annotations, probably issued at the time of Lu Buwei, c. 230 BCE, has today a print paper 2004 edition. Here is the modern edition, 2000 years later, citation in full:《管子·轻重甲篇》,黎翔凤:《管子校注》(下),中华书局2004年版,第1425~1426页。Also see, 参见《史记》卷6《秦始皇本纪》,许嘉璐主编:《二十四史全译·史记》(第一册),汉语大词典出版社2004年版,第77页。/ ]

Modern variants of the same One Nation, Two Emperors rule is everywhere. In Hong Kong, it’s called the One Country, Two Systems, basically a device for power sharing between the Beijing central government and the cabal of Hong Kong’s oligarch of bankers, property developers and public officials.

Internal to Hong Kong, the local oligarchy rules; externally, as in foreign and military affairs, it’s Beijing.

But in banking and finance, in the local USD economy, the buying and selling of property, government budgets, and especially the monetary system of credit and currency issuance (i.e. the HKD), these are all externally provided for, supplied and controlled by the US government no less. The US Federal Reserve turns off the tap of USD supply tomorrow, Hong Kong goes bankrupt the next day — literally.

So the One Country, Two Systems, though it vests power in a local government actually hides and lent legitimacy to being ruled by agents of US power. In short, a colony.

It gets worse. Behind the face of various US presidencies there is, again, the same cabal of bankers and corporate tycoons, just as it is in Hong Kong. In particular, executives of JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, BlackRock and Goldman Sachs are constantly rotated into the White House Cabinet, serving as secretaries for Commerce, Treasury, and Economic Planning and as varied department heads. Under Barack Obama, for instance, the White House counted nine such appointments.

Here though is the penultimate difference between the One Country, Two Emperors problem in China 2,200 years ago and US today.

Lu Buwei spent his money, gained from buying and selling grain, fabrics, weapon materials and land, to buy himself influence and, hence, a place in power. This is because the merchant class to which be belonged were widely scorned, standing near the bottom of the social status, one rung above a vagrant, two rungs below the peasant.

State rule in his hands, he continued to convert his wealth into Qin state power, for example, supplementing grain supplies to the army which, on today’s scale, would be still the largest: a million foot soldier under arms, backed by a calvary on horseback of some 20,000.

The US One Country, Two Emperors problem flips the Chinese version around: Americans treating the government as some jelly bean jar where everyone dips in their hands, helping themselves to the largesse. That is, BlackRock, Larry Fink et al got rich in, and from, a government that costs them not a dime, and without ever having to solicit a single ballot vote. For that, the western electoral pretense of democracy, it is the job of frontmen like Obama, Joe Biden and dozens of other presidents before them. Hence, it means nothing to them, nor would Americans die by the millions, to launch a war once yearly or bomb the lives of Gaza into smithereens. On the contrary.

Harvard, Chicago and Stanford scumbags in political academia like Francis Fukuyama and John Mearsheimer have a fancy name to veil this murderous American fraud and plunder: the International Politics of Realism.

It was the father of the Ying Zheng emperor (Qin Shihuang) who had brought Lu Buwei into public office, so the latter simply continued hiring Lu, in true Chinese filialness when father died. Ying Zheng watched Lu merged private finance and State power, but ignored an irrigation canal, a pet project of the emperor, to open new farmlands, expand grain output that, invariably, would bring down prices, affecting in turn the volume of trade. (That situation is identical to Hong Kong wherein, preaching free market, successive generations of governments rarely bothered to lay down a single brick that, in aggregate, would drive down mortgages and rents from increased construction and more housing supply.) Lu issued edicts and promulgated laws without consulting Ying Zheng, and he hired whoever he fancied.

That is, in short, a misappropriation of State resources, weakening its power as a result, rather than husbanding the same to expand that power.

Predictably, wariness grew into suspicion. To remove Lu Buwei, Ying Zheng waited for an opportunity and an excuse, namely that some people Lu had brought into public administration, including few senior ministers and army officers, had plotted to remove him.

That’s when the One Country, Two Emperors problem came to a head. The rebels were arrested, tried, and publicly executed almost immediately after, their persons made to lie flat on a platform then chopped into half. The chief plotter, of ministerial rank, was put to death by 五马分尸, his limbs and neck tied to five horses, driven to go in five directions, pulled apart. Soon after, in 235 BCE, six years before the reunification of China by Ying Zheng, Lu Buwei was stripped of his premiership post, all pensions and benefits withdrawn then exiled into a patch of land where he grew his own food and vegetables.

Thus ended for 2,200 years the One Country, Two Emperor experiment, only to be revived in Hong Kong in 1997. Today, sponsored by the Hong Kong government, nurtured especially in academia and in corporate boardrooms (think HSBC and Cheung Kong 長江, Hang Lung 恒隆, Jack Ma, et al), and thanks to American spread of liberal indoctrination, the Lu Buwei class is back. Some worry, this class is on the ascendant in China proper. An inevitable result: the same rule of two systems, two emperors existing in one nation have re-emerged in Mainland China.

It is about this class, and fighting against them, that the rest of this essay will be devoted.

[Below is the epochal confrontation between the free market capitalist financier in Lu Buwei and the traditionalist, legal scholar-official Li Si just appointed by Qin Shihuang. Note Lu’s initial, contemptuous regard for Li Si — “you have something to say, Li Si?” — who would one day replace him.]

*

THE PROBLEM WITH REFORMS

敕天之命,chitian zhiming

惟时惟几 weishi weiji

Without knowing to read them in the Chinese, or knowing their meanings, the rhythm in the couplet are self-evident. First line: chi = zhi. Second line wei, then wei again reinforced by shi and ji. The English, after Geoffrey Chaucer (14th Century) then followed by William Wordsworth, like to imagine they invented the iambic pentameter. Wrong….

There are thousands more of those Chinese lines on strips of bamboo, others etched on stone tablets. The pentameter above is from the Shang era circa 1600 BCE to 1046 BCE, since compiled into the shangshu 尚書, written some 2,500 years before Chaucer.

What’s more astounding isn’t the literary quality so early on or their novelty, which is by now standard in Chinese culture, but the subject at hand. Which is, political philosophy. That has never been match since in any English (and western?) literature.

In translation (mine), the two lines might read like this:

Heaven commands, Fate complies,

For the Seasons, for the Many

It is this inherited intellectual culture that the Chinese today has to work with because those lines read like they had been written yesterday.

Interprete how you will into those lines, one thing is inescapable. That is, its political or, if you like following the crowd, its “democratic” quality and flavor. It reads like an entreaty or a plea to Chinese rulers, to carry out humane policies then and today still, which many Chinese and every Whitey alive (if knowingly) attributes to Confucius: Be like the North Star in your rule, and everything will revolve around it.

Confucius never made the claim as an inventor of Chinese political philosophy. On the contrary, he, in his own works (Analects, most famously), repeatedly referred back to the Shang and Zhou era writings, the sources of his thoughts.

Contained in the code name or in the overriding theme, named jueding 《决定》The Decision, of China’s Communist Party (CPC) Third Plenum, are the same unmistakable Shang entreaty: Heaven commands, Fate complies / For the Seasons, for the Many. In their crude English language, the Third Plenum is asking: follow the Party line, follow the Decision.

There are more from the said Shang era that the CPC uses, perhaps instinctively, but never attributes (read the Third Plenum’s Decision or resolution here):

德惟善政,政在养民 déwéi shànzhèng, zhèngzài yǎngmín

四海困穷,天禄永终 sìhǎi kùnqióng, tiānlù yǒngzhōng

In translation (again, mine):

In government Virtue lays, in the people the Government lays

Within the Four Seas the Destitute tires, for Heaven’s Road stretches to no end

Yet, from the CGTN and Global Times news rooms run by Anglophile motherfuckers, none of that is ever told about the Plenum, whether to the Chinese or to the world.

Instead, they go on and on and on and on about “impact” on the world, and how great is the Plenum bringing “credibility” and “stability”. And all this is regurgitate in full by the equally stupid Anglophone media. We, of course, know the origin into this state of affairs: liberal Anglophiles have their western agenda to fulfill, stupid individual Whiteys with their racist egos and doctrinal prejudices to massage.

Inside the CPC, however, is the sense that all the talk of reforms today are not the kind of reforms carried out in the last 40 odd decades. The word gaige 改革 may be written and read the same as it was a generation earlier but to mean it the same then as it is now, would imply nothing had changed, or worse, prior reform had been a failure.

If, however, reform were to be spoken off in a difference sense then it had to mean differently. The core of the 1980 reform agenda was clear cut: lift up everybody. But its successor program, contained in a meandering, convoluted form called “comprehensive deepening of reforms” or 全面深化改革 still doesn’t answer the question: Where to next?

Everybody knows what we Chinese want, essentially more money and a better life. And here is the shopping list for the new reform agenda (specifics in parentheses, mine):

education (focus on science and technology)

politics (economics of distribution, asset allocation)

law (finance and land laws)

culture (history and philosophy)

society (welfare, health benefits, rural development),

ecology,

national security (military advances).

Where is all that to take the Chinese nation? No CPC leader ever attempts to answer that question because nobody knows until we get there. Which leads to a problem that, as the years and decades roll by, has become increasingly self-evident: What to do with the effects of reforms retarding the object of reforms?

All this is hardly a contradiction; it’s Daoist truism: long and short, high and low create, beget and define each other.

Inequality, which is a consequence of reforms, now retards reforms. The US Dollar retards reforms, as do America, the local Rich and the Shanghai and Hong Kong landed oligarchy; they openly admit to it. (One has only to listen to Jack Ma or Henry Wang 王辉耀 or Carrie Lam of Hong Kong for example.) Anglophiles want to push reforms — economic liberalization, free market finance, land sales, highest bidder principle, and so on — any of which they know, or ought to know, would ruin reforms objectives. That’s a demonstrable, empirical fact: But, break from rich, makes you better, much better (see, for example, chart below).

PUTTING THE LAW ON TRIAL*

For evidence to see if the statement above is true or false, go back to the shangshu 尚書 lines.

The body of the Plenum’s Decision contains 60 articles and proposes some 300 “reform measures” 改革举措. These recommendations are to be used in later law-making and to function as guide for execution of Beijing’s policies at municipal and county levels. A chunk of them has to do with devising laws to bring about equitable distribution (also see this). How, for example, is a woman after divorce to retain some measure of rights to a family’s immovable and movable real estate?

This is a conventional, social and a historical issue dispersed across and varies according to families, villages and clans. The State would like to universalize it, adopting a single standard like Global Times’s Hu Xijin would like to have it, raised as he was in a biblical voodoo diet following the White man. Even there, following the West, bracketing it as a legal issue, there are as many answers as there are cases thrown up yearly. Should the problem be resolved within the Decision guidelines under “Society” (#5 in the table above) or Law (#3) or even Politics or Culture?

Nobody is now sure, thanks to the Plenum because of the Decision’s paucity of clarity, preferring instead to stick to the politically safe line — Chinese characteristics — an ideologically, liberal neutral term passed down from the Deng Xiaoping era.

We Chinese are reticent to give a straight answer to the divorcee’s problem, preferring instead that the Law takes a back seat for the reason that a single rule constraints the answer rather than help it. (Hong Kong is an exception to this rule because of the colonial imposition of White man’s law.) Hence, to us Chinese, settlements 和解 hejie are never to be forced but simply requires the unfastening, or jie 解, of a complicated, knotted situation peaceably, or he 和 (pronounced her).

But not the White-imitation liberal class, however. Proclaiming liberal victory in the Chinese edition of the Global Times after the Plenum, their chief propagandist Hu Xijin had this to say:

“《决定》中没有公有制为主体’的表述。。。” Translation, “In the main body of the Decision there is never anywhere this statement, ‘public ownership’”

Hu’s liberal message told to the Chinese public as well as illiterate, unemployable Anglophone bloggers feathering Hu’s nest (think Laura Ruggeri, Alex Krainer et al who like to believe they are Chinese “experts” when they can’t even write their mother’s name in Chinese) and the subversive Whitey and Anglophile editors at Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post is clear:

“…socialism in China will have to, hereon, retreat. In its place, private ownership of the Chinese economy and society will flower! And all that is, by order of the CPC’s Central Committee.”

It is academic, citing verse and line from prior CPC statements, to point to the falsity of Hu’s insinuation because truth is not at stake in the man’s way of lying — an established, standard practise in the Whitey way of portraying China.

What’s at stake is that the Third Plenum has taken the first steps to finally break the impasse and shatter the taboo, highlighting the adverse ramifications brought out by four decades of Deng reforms.

Except for this problem in the Decision that the Chinese take exception to: Which is to actually define the (unhappy) fallout from the reforms and naming the domestic enemies of China and the enemies to the intent of reforms. (Recall the Rectification of Terms/Names in the Analects.) Hu Xijin, Ronnie Chan, Henry Wang are just some of them, and it’s no coincidence they display the same dog and pony, song and dance show each time the word reform is raised.

Of course, the CPC has its reasons for being as vague as they can get away with. Their job is like finding the universally, perfect law to guarantee the rights to a family’s real estate after a woman’s divorce.

Finding no such universal laws, they turn the Decision into a wordy tome of 6,000 words in the English (rule of thumb word count conversion: 2 English words to 1 Chinese script). Which, of course, most Chinese find fucking boring to even look at the title!

So the vast majority of us Chinese mortals skip the Third Plenum and its Decision, which is, in its turn, left to the provincial, municipal, county and village authorities to sort out and do what they will with it.

Does that mean we Chinese will get another 40 years of shit? Does that mean the imitation Whiteys and their liberal landlords, bankers and brokers peddling voodoo bonds will now get their way? Does that mean the White man can come in, step over all of us, roaming through our homes and in our backyards for choice properties to buy and sell?

No, we refuse! (See Part One, Decision of the Plenum.) Let there be no doubt: China, including Taiwan and Hong Kong, belongs to its people, all 1.4 billion, not the CPC, and belonging only to the Chinese, with blood and ancestral ties to the land.

To the CPC, we say, stop; we say, fuck you, for when we see foreigners next door, we’ll kill them! It will be the Boxers 義和團運動 all over again because we hadn’t come this far, 3,000 years since the great Duke of Zhou 周公旦 (r.1042 BCE) and after him the Da Qin Ying Zheng (r.221BCE), to watch yet again a Qing China being repeated, the nation dismembered, everyone destitute and land and bodies sold off in chunks to the highest bidder, each one of them private and foreign.

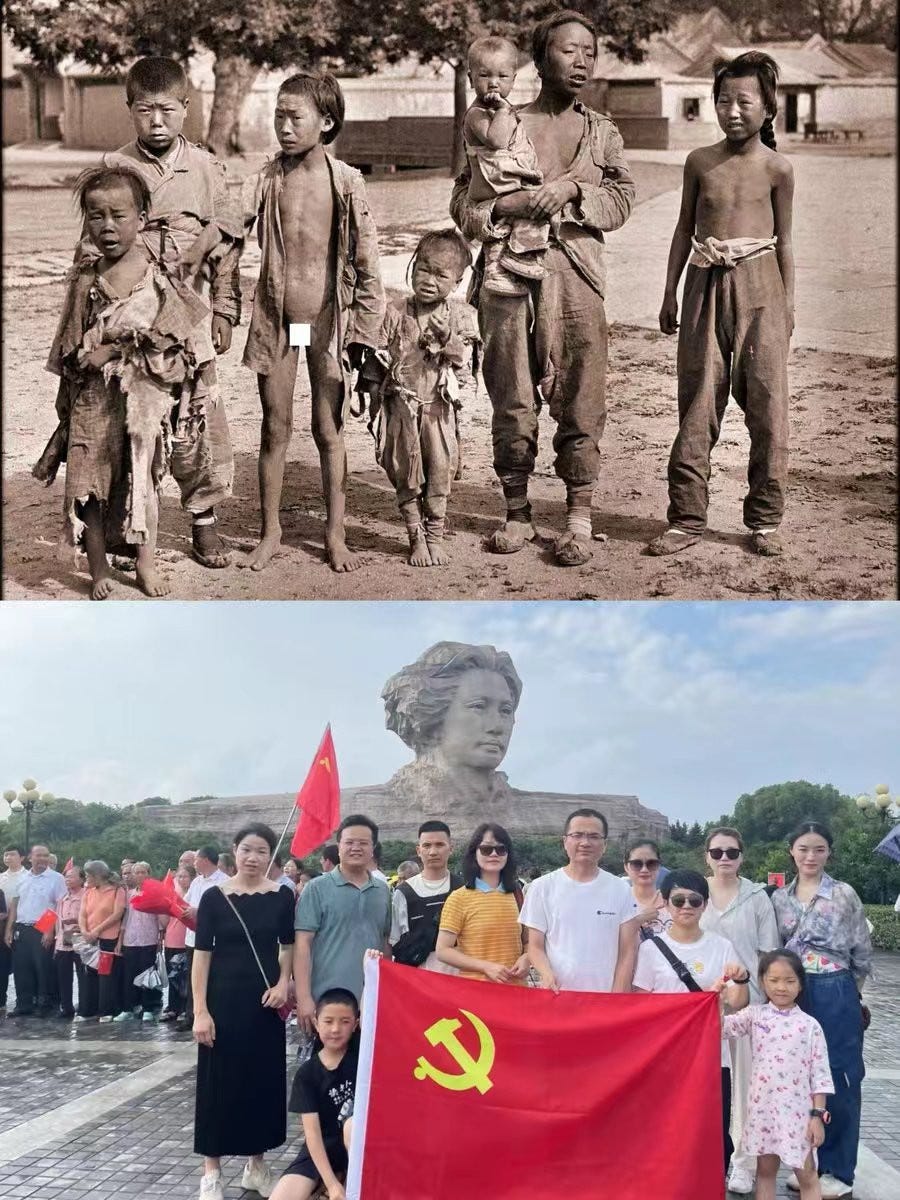

The CPC has done exceptionally great and noteworthy deeds (image below) over which our ancestors will be proud off for the next 5,000 years, so, don’t spoil it because of some motherfucker in our ranks named Hu Xijin. We’d kill him and hang his head on Tiananmen!

(*The term is borrowed from Franz Kafka’s Before the Law, 1915.)

THE RICH IS NOT TO BE REFORMED BUT…

The Decision is noteworthy in one crucial respect. It’s not binding.

The CPC doesn’t issue laws. This is the work of the National People’s Congress where the party has a dominant role which, in its turn, relies on the Central Committee for direction and a raison d’etre.

If the party wants to dabble in laws, the work is never ending. So the poor divorcee, worried about her rights to the family’s real estate, will never ever get a definite answer. And, if there is ever any answer, there will be as many as there are divorce cases kicked off each year. The issue then is not the post-divorce settlement but the divorce itself, that is, the family. Kongzi was right: sort out the family, the nation sorts itself out.

In today’s urban environment, answering the divorcee’s rights spills over into mind-boggling array of considerations: inheritance laws, capital gains tax, insurance, not to mention touching the businesses of China’s feudal rent-seeking class of bankers, landlords, property developers and the like.

Our party leaders want to try to reach an ideal society, which heaven forbids, nobody knows how it looks like, not even with the hindsight of the shangshu, the lessons of Lu Buwei and so on. Thus the Plenum’s Decision is full of vague allusions to that idealization, with little in concreteness. Perhaps that, too, is alright!

The problem of idealization isn’t just with the CPC. As long as the Chinese have been a nation, we, the native Peoples of our Motherland, recalling the sacrifices of our ancestors, parents and brothers and sisters, have been left to guess as to this ideal destination place: Where, too, would they like to end up?

Truth be told, the ideal destination doesn’t exist. Kongzi said so, as did Laozi and ten out of ten of our intellectual forebears. We may attempt to minimize muddling through national life but some problems are as clear as Taishan against the morning ray of lights.

The Rich must go. We see the results of their work in every corner of the world, from Timbuktu to the Andes. (For an explanation into that critical aspect of the Decision, see here, in the Chinese of course: 新一轮财税改革任务清单公开,涉及个税等20项重大改革, 观察者网 guancha, 2024 July 22. https://m.guancha.cn/economy/2024_07_21_742225.shtml.)

Those results stare at us daily, out of Hong Kong in particular, but we choose and we pretend they aren’t there. But the reasons to destroy the Rich are as plain as day: the more their liberal, White, western agenda advances, the more retarded is the welfare and interests of everyone else.

That is a statement not of opinion but of demonstrable, verifiable, empirical fact.

If, even that is hard to stomach, then we are left to retreat to the entreaties of our forefathers in the shangshu: “In government Virtue lays, in the people the Government lays / Within the Four Seas the Destitute tires, for Heaven’s Road stretches to no end.”

If that also doesn’t work, consider the following logical progression, beginning with this proposition: As long as they are billionaires around (Bill Gates, Jamie Dimon, Jack Ma and so on) there will be no rest for the endeavors of the world.

Yet, if we line all of them against the Great Wall and shoot them, the issues of poverty and economic distribution will not resolve readily.

Many of today’s Chinese noveau riche are CPC card-carrying members, Jack Ma, a former teacher, being a notorious example. Hu Xijin another. We created them, so we are entitled to take them down not as an entitlement but because we had willed them into existence. Kill them today, the law of averages will replace them.

The CPC’s current membership-roll is 99 million. Even if the chances are one in a million the CPC will produce another Jack Ma next year then it will still get 99. We could shoot all of them but the statistical probability remains such we’ll again get (in just the CPC alone) another 99 Hu assholes types feathering the rich from Guangdong to Shanghai.

That is, because the Rich are dispensable, we don’t have to worry they won’t exist anymore as a class which, some argue, is indispensable to the economy’s finances. This is patently false and a doctrinal lie but that’s how the Stupid and the Illiterate conclude.

(a) There is no poverty without wealth and vice-versa. This follows the same empirical logic that the West won’t be wealthy if Rest of the World weren’t poor, and from whom the West had plundered. Michael Parenti: “The poor are not underdeveloped, they are over exploited.”

Parenti’s proof follows the same Daoist principle: long and short, high and low, day and night, rich and poor, Being and non-Being create, beget and define each other. One alone can never stand to exist alone; similarly it is for the rent-seeking class if there was nobody from which they can sponge off.

(b) One country, two emperors. This, again, is from China’s history, specifically the Qin dynasty (c.750 BCE-206 BCE). The argument against it has gone on for 2,0000 years so there’s no need to go back to it except for this point: The Rich running the nation does not swear on the principles of the Mandate of Heaven, just as Bill Gates doesn’t need to care if America lives or dies so long as he can made money — his raison d’etre — which is all the more easier on property over dead bodies.

The Chinese way isn’t like that. White people attach power only to rule whereas we Chinese, exceptional in this world, attaches ethics to power and, hence, to rule. This is the essence of the Mandate of Heaven the Chinese have granted the CPC. We give the party power, we are also entitled to take it away! So, watch out for your little Hus and your rich Wangs.

All said and done, the Decision will be supported only because what else is there?

The Decision — for let this be said — is very, very, very bland in several ways: mind-crippling long, tendentious, tired cliches, bad (Chinese) written styles and organization, and, above all, repetitive terms, usually repeated a million times from earlier announcements or media statements.

The Global Times is not permitted to interprete it any how they like. It doesn’t own the CPC, much less the Chinese nation. (See, for example, this refutation of Hu Xijin: 赵磊:驳胡锡进们所谓“《决定》没有公有制为主体”的谬读 - 红色文化网, Red Culture 2024 July 24). Which leaves the problem of reading into the Third Plenum’s Decision unanswered, a question that begs itself: What's there to read? Or to look out for?

Short answer, nothing!

But, the Chinese, always so ingenious a people, smarter than nine out of ten public officials, we will, to imitate the Chinese, look for two things: (a) metaphorical allusions or a turn of phrase harking back to some historical or literary past, the farther back the better, and (b) characters or terms rarely seen before or used in official statements. Since the outside world is unable to do either (a) or (b), the Plenum's statement, even in its (English) translation, is impenetrable to foreigners. We don’t care about them.

Here’s an example: 山高路远步履坚定。。。That was Xi Jinping, talking about “the mountains are high / the road is long” (山高路远), a favorite phrase of the introspective Chinese each time we arrive at an inflection point. It was in a speech, July 18, urging, “don’t waver,” 步履坚定 Xi says, to pass the resolution on the Decision 决定.

It’s that pair of phrases again: jianding 坚定 and jueding 决定 . Hence, 山高路远步履坚定 shāngāo lù yuǎn bùlǚ jiāndìng, reads in modern translation as, “The mountains may be high and the road ahead long, let’s press ahead, never wavering for a moment.”

On its own, the metaphor cries out to be answered: What’s that big-deal Decision Xi urges everyone to stick to?

The answer is anti-climactic: simply, in Xi’s words: 从“全面深化改革”到“进一步全面深化改革”. In English, in italics, “from ‘comprehensive deepening reform’ to ‘further comprehensive deepening reform’. In other words, simply restated, to continue (进一步) the existing reforms.

That’s all that’s to it in the Decision, which is the thrust of the entire communique. The rest are just (superficial) details.

Was Xi dramatizing or overdramatizing? Yes, on the face of it. But, here’s the catch, also provided by him: “到二〇二九年中华人民共和国成立八十周年时,完成本决定提出的改革任务。” Translation: “By 2029, on the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, the tasks of [our] reforms, proposed now in this Decision [决定 jueding, that word again] would be completed.”

What?

Let’s cut to the chase: The sum of the CPC’s work – often rendered as “comprehensive deepening reform” – makes up by what's now a standard statement: “要把全面深化改革作为推进中国式现代化的根本动力” Translated: “We must take comprehensive deepening reform as the fundamental driving force for promoting Chinese-style modernization.”

We, the natives of China, will hold Xi to his words!

That is, reforms don't exist for their own sake but to serve Chinese-style modernization. In the term, hence, Chinese is the emphasis instead of mere modernization. That, in its turn, is to see through the rejuvenation of Chinese society, culture and civilization from 1949 through to 2049. The year 2049 is the 100th Anniversary of the PRC, which is modern China.

In another manner of saying the same, the Plenum is the opening in last leg of a work in progress of total social, economic and political change of Chinese society, the work informally marked for closure in 2049. Hence this push for the Third Plenum, since to get to 2049, the Plenum’s Decision must first get pass 2029 which is its target date.

China's 2023 GDP in real, nominal terms (inflation adjusted) was US$12,200, some statistics say US$13,000. Growing at 5 percent a year, US$12,200 would double to around US$25,000 in 20 years. At the 25,000 mark, China’s standing would jump to about 40 of 190 countries from around 70 today.

Faster than that, however, growing at 7 percent a year, GDP per capita would double in ten years time, circa 2039. At that rate, China in 2029 would reach the half-way mark of the 2049 target. The century of rejuvenation would be realised thus in 2039, ten years ahead of schedule!

Is that possible? How to get there, ahead of time — especially before the US, NATO and the White man blows up everything?

All this explains the urgency and the stress of the Third Plenum. Since we simply don’t know what’s to become of the world, it makes the Third Plenum Decision greatly momentous — equal to or perhaps surpassing in ramifications to Deng Xiaoping’s 1980 reform and opening up.

It’s the world, thus, that has affected the Third Plenum not, as Global Times writes, the other way round, “bringing certainty” to the former. Hu is outright lying!

Equal to the urgency, is the type of reform because it has a bearing on the outcome. That is, how China will look in 2029, 2039 and 2049? The CPC is insisting “Chinese-style” reform because no other models — not liberalism, not free market capitalism and not communism — will take the Chinese there, and there are 3,000 years of written, demonstrated proof to that effect. Ask Lu Buwei!

For at least 1,500 years until circa 1750, China stood as, by numerous economic measures, the world’s wealthiest and biggest, with 30 percent of global GDP output. (Look up, for example, Kenneth Pomeranz in The Great Divergence, Princeton University Press, 2000.)

Now comes the real work, fulfilling the Will of Heaven’s Mandate. That Will lays in Chinese ethics and in actual Chinese political culture and its sociology and not in dithering over how much more should the Rich get from slicing the Chinese pie. We are done with placating the Rich — What more do they want? — especially the Banana Anglophiles, yellow outside, white inside!

If we — and the CPC — fails, then the world’s Greatest Civilization will, once again, be reduced to that image below, a pathetic sign.

Those whitey lines must never, never, never be permitted on Chinese soil ever again. We swear, at the graves of our forefathers, that the next such sign in the Shanghai Pudong international airport will read: Dogs and Whites No Admittance — with Hu Xijin’s skull dangling from it, flanked by the heads of the top shareholder and the chief editor of the South China Morning Post! Very Roman and Christian indeed, exactly the way they worship their god.

*

《長安十二時辰》

Even in one of its most prosperous epoch, the Tang era 1,500 years ago, and still minding its own business, China was not spared of foreign intervention which was invariably aided by traitors at home. In the old days, we kill them. So we must today. The humongous sacrifices of our ancestors, paid for in blood and in millions of broken homes, that people kept China intact and at peace must not be in vain.

*